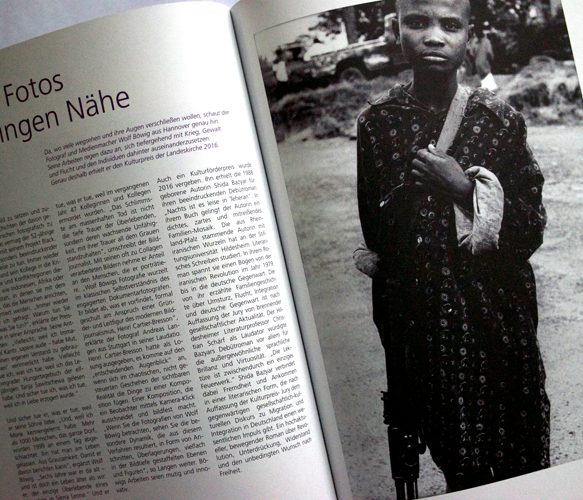

FAZ.NET; 19.1.2018 – „Wahrhaftig sein, Auge in Auge“

Wolf Böwig ist Fotograf, Kriegsreporter, Weltreisender. Er hat die grausamsten Orte der Erde gesehen, aber auch ihre schönsten und geheimnisvollsten Winkel. In seinen Tagebüchern hingegen findet er zu sich …

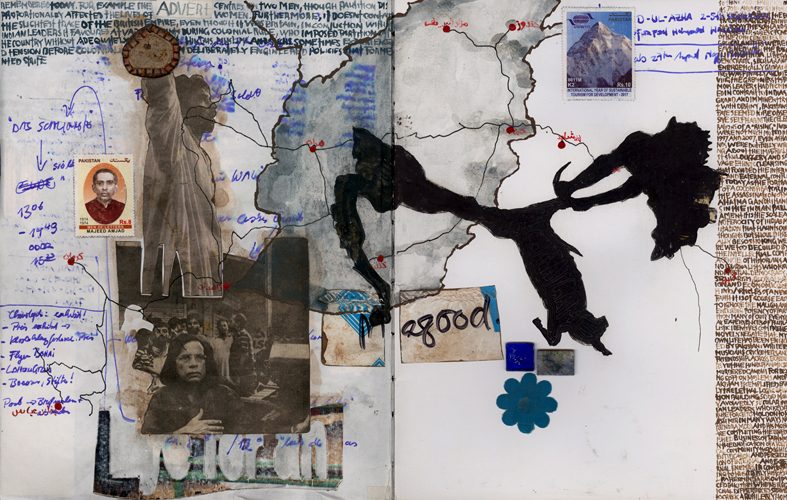

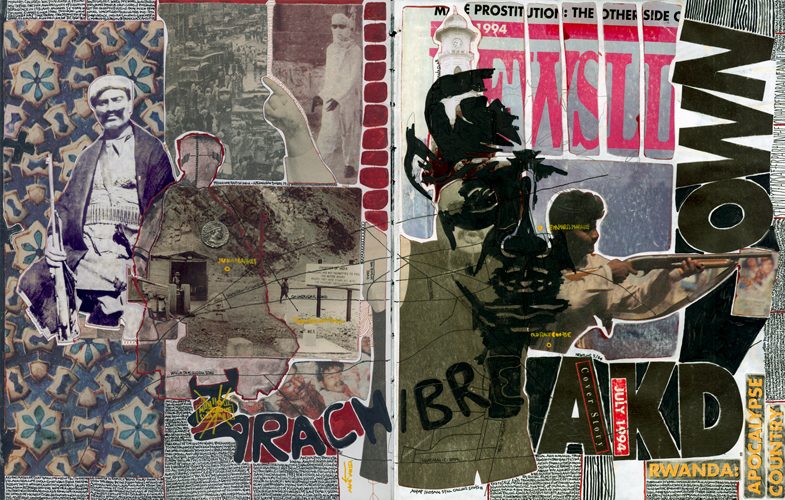

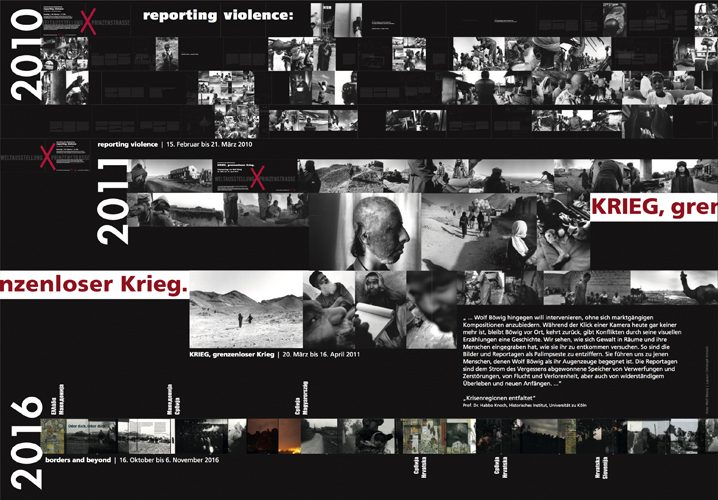

Doppelseite für Schauspiel Hannover – Ausstellungen 2010 bis 2016

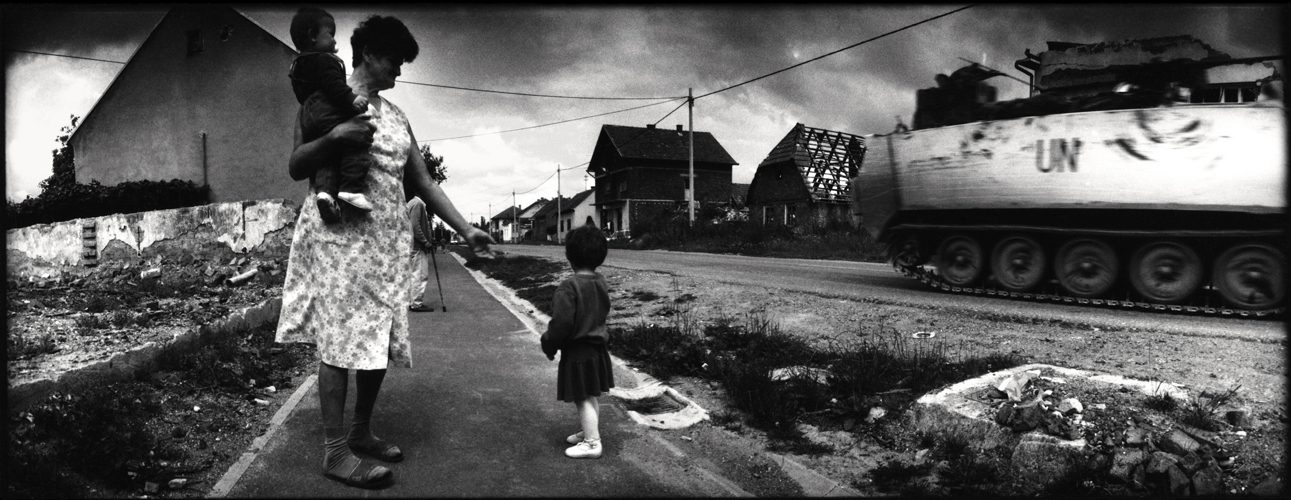

reporting violence

15.Februar bis 21.März 2010

KRIEG, grenzenloser Krieg!

20.März bis 16.April 2011

borders and beyond

16. Oktober bis 6.November 2016

Pedro Rosa Mendes on Wolf Böwig’s Photojournalism

„

…

I strongly believe – having never discussed this much with him – that Wolf’s uniqueness derives from his photojournalism being a radical form of self-overcoming. He’s saved from nihilism albeit living a lifetime in close encounters with different forms of human bestiality. There is thus a quality of the superman who built „a power over oneself and over fate“, which has „penetrated to the profoundest depths and become instinct“ (On the Genealogy of Morals).

4.

T.E. Lawrence, whom we are both very fond of, sensed madness near, even if in the form of wisdom and alterity, as „it would be near to the man who could see things through the veils at once of two customs, two cultures, two environments“ (Seven Pillars of Wisdom).

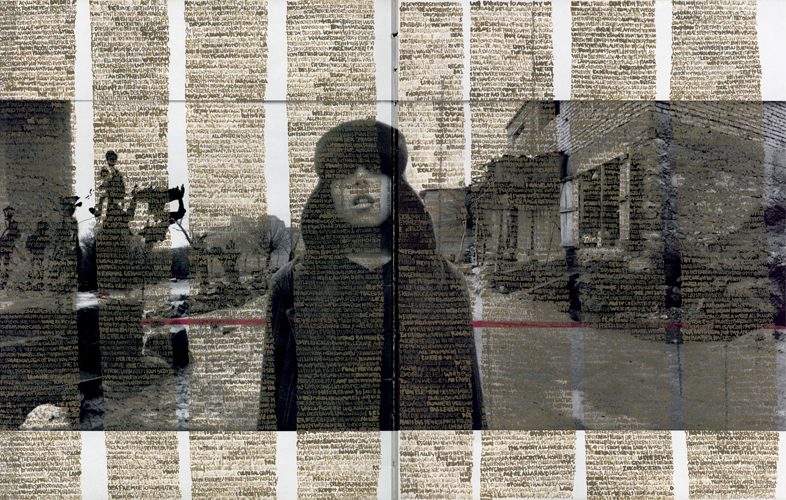

Borderlines of all kinds, from mental to political to cultural, are central to Wolf’s account of the human nature we all inhabit and share. It is that inherent madness that he crudely displays, with layers of historical, political, emotional and linguistic complexity.

Throughout Wolf’s extensive body of work, human reality emerges as revelation, vary rarely as exposure, whereby each photographic moment captures the accumulation of references that define a sense of individual, collective and social identity – identity being that ultimate sovereign form of madness over one’s self.

…

„

Kann man mit dem Magnificat regieren?

Über eines der politischsten Lieder, das je gesungen wurde

von Mathias Greffrath (NDR Kultur, Glaubenssachen 14.1.2018)

…

Mit dem Magnificat Politik zu machen, das bewahrt nicht vor Verzweiflung. Aber wer mit dem Magnificat im Geiste Politik macht, der vertraut darauf, dass es durch die Jahrhunderte den Zusammenhang eines nomadischen und missionierenden Gottesvolkes gibt, das sich lange vor ihm auf den Weg gemacht hat und lange nach ihm weitermachen wird, das an die Prophezeiungen und an die Vorbilder glaubt, die Teil der Überlieferung sind. Maria glaubt. Das heißt: Sie lässt sich von der Tradition ergreifen, versteht sich als Teil einer Bewegung, die lange vor ihr begonnen hat, und die mit ihr nicht endet. Solcher Glaube trägt und er macht enttäuschungsfest. Wenn ich scheitere, heißt das nicht, dass ich unrecht hatte; wenn ich unterliege, unterliegt nicht die Wahrheit; wenn ich untergehe, werden andere weitermachen

…

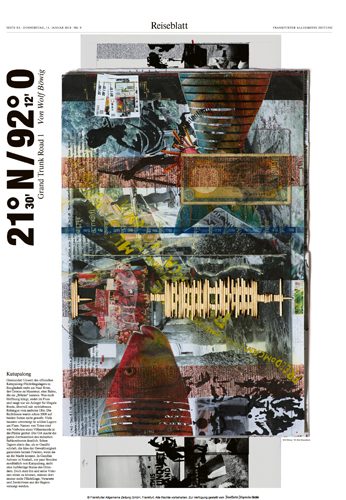

FAZ; 11.1.2018 – Wahrhaftig sein, Auge in Auge

GTR Teil 1

von Habbo Knoch

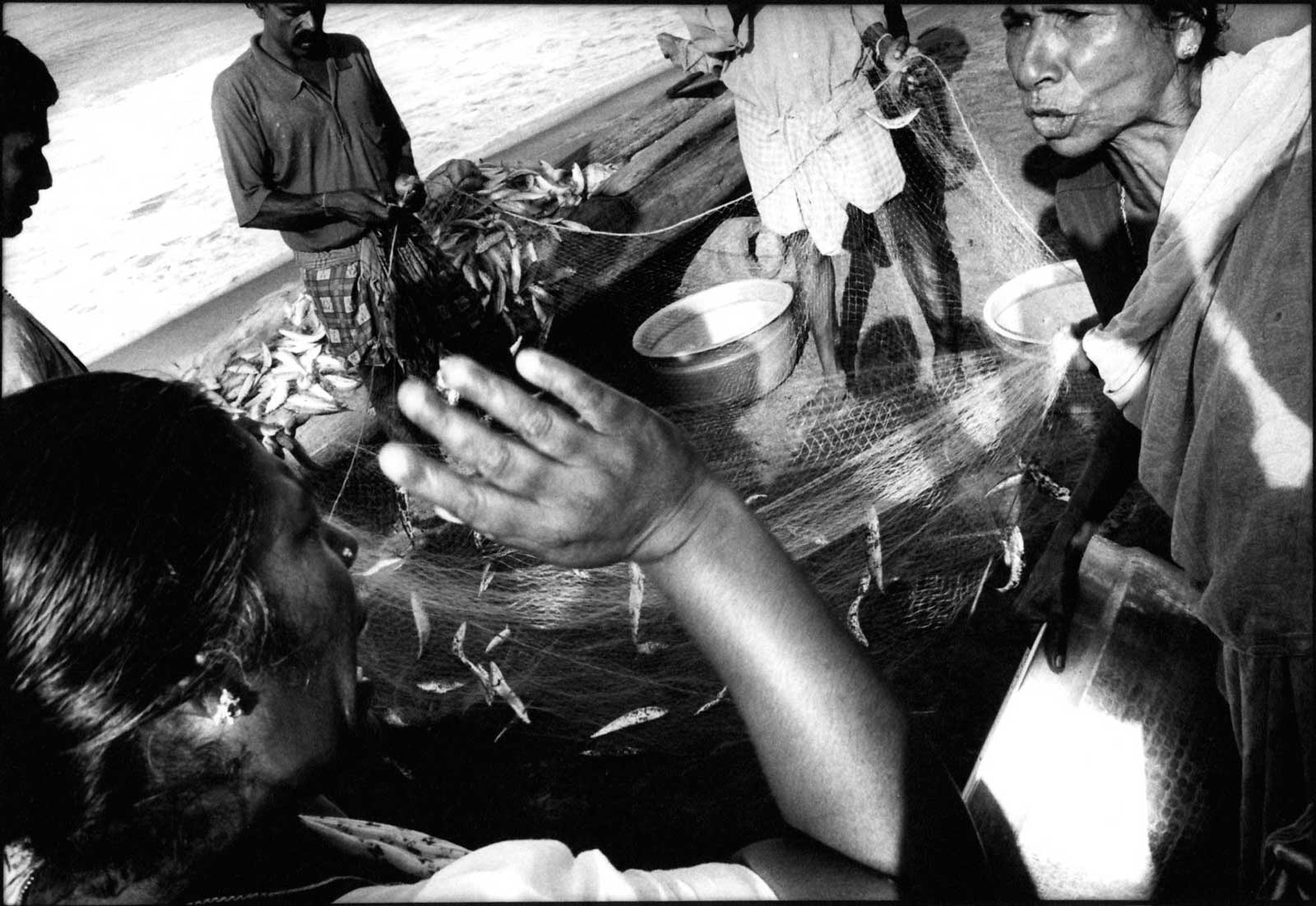

Kutupalong – Gestrandet: Unweit des offiziellen Kutupalong Flüchtlingslagers in Bangladesh steht am Naaf River, der Grenze zu Myanmar, eine Ruine, die sie „Brücke“ nennen. Was nach Hoffnung klingt, endet im Fluss und taugt nur als Anleger für illegale Boote, übervoll mit vertriebenen Rohingya vom anderen Ufer. Die Rechtlosen waren schon 2008 auf beiden Seiten nicht gewollt. Viele hausten unversorgt in wilden Lagern am Fluss. Namen von Toten sind wie Vorboten eines Völkermords in die Pfeiler geritzt. Der Ort macht die ganze Zerrissenheit des indischen Subkontinents deutlich. Schon Tagore ahnte das, als er Gandhi schrieb, die Idee der Gewaltlosigkeit garantiere keinen Frieden, wenn sie an die Macht komme. In Gandhis Ashram in Noakali, ein paar Stunden nordöstlich von Kutupalong, steht eine halbfertige Statue des Gründers. Doch statt ihn und seine Visionen ehren zu können, müssen dort immer mehr Flüchtlinge, Verarmte und Zerstrittene aus der Region versorgt werden.

„I believe in the sacredness and dignity of the individual. I believe that all men derive the right to freedom equally from God. I pledge to resist aggression and tyranny wherever they appear on earth. “

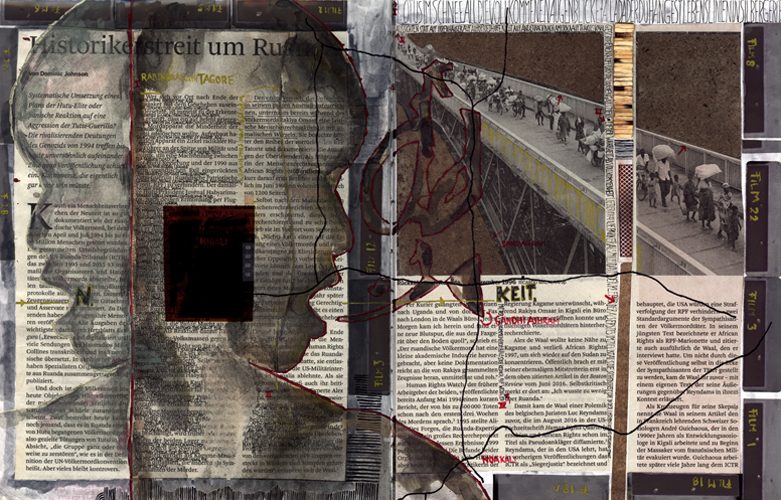

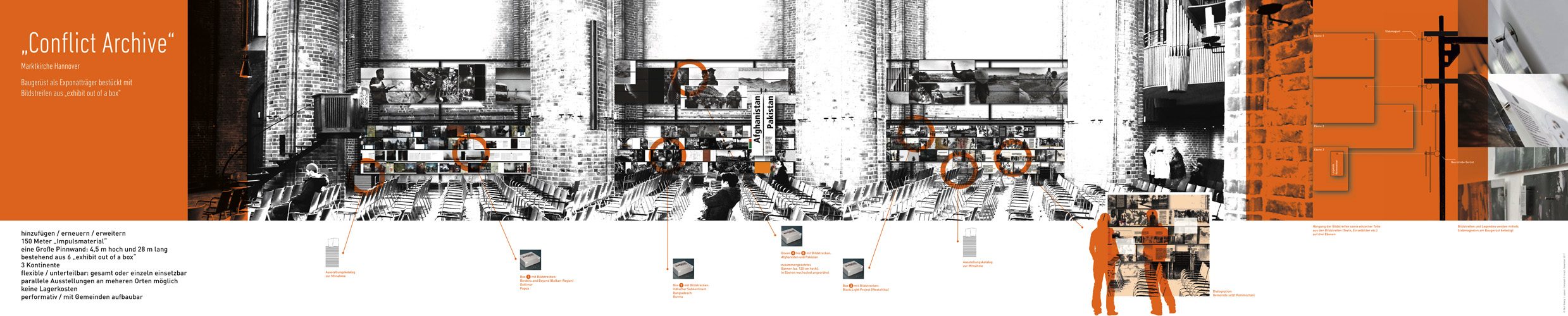

conflict archive – Ausstellungskonzept

„Kontext: als Erinnerungskultur den Gedanken eines „offenen Archivs“ umzusetzen, teils als Kunstprojekt, aber mit dem Ziel der Dokumentation; „Archiv“ war dabei seiner elitären Bedeutung (als „Staatsarchiv“) enthoben und Bürger gebeten, Dokumente, die sie für relevant halten, in das „offene Archiv“ einzubringen zu meinen gestellten Arbeiten. In diesem Rahmen läßt sich der Ansatz des „conflict archive“ in die Open-Access-Debatte einrücken: Bereitstellung und Zugang wichtiger als die „Hoheit“ über das Material.“

Borders and beyond – ein musikalisch-verbaler Grenzgang

“ Wir haben in unendlich vielen Verträgen den absehbar richtigen Umgang beschrieben und verabredet. Und doch sind Kriege und Konflikte unaufhörlich Teil unserer menschlichen Realität. Güte und Wahrheit sind die ersten furchtbaren Opfer.

Wir haben den Krieg nicht beseitigt, nicht einmal dadurch, dass wir uns seine Schrecken immer wieder vor Augen führen. Mit Wolf Böwig kommt nun ein renommierter Kriegsberichterstatter ins Kloster Loccum und mit Bettina Pahn und Joachim Held zwei international gefeierte Musikvirtuosen und Echopreisträger. Ein Wechselspiel zwischen Wort und Musik als Grenzgang zwischen den Fronten. …“

7ter Oktober 2017

18.30Uhr

Kloster Loccum

Stiftskirche