BLACK.LIGHT PROJECT

„Wer im Schatten bleibt, der stirbt“

Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, 14. Januar 2012

Andreas Platthaus

“

Vor einem Jahr, Anfang 2011, sah alles so gut aus: das Projekt sowieso, aber auch die Finanzierung. Heute sind die Vorarbeiten fortgeschritten, und das, was man nun wirklich schon sehen kann von „Black. Light“, sieht noch viel besser aus, als es die Anfänge vor einem Jahr vermuten ließen. Doch mit dem Geld sieht es schlecht aus. Und das, obwohl gleich zehn bedeutende Illustratoren an „Black.Light“ beteiligt sind. Es ist typisch: Da interessieren sich einmal Künstler und Journalisten aus der Beletage des Lebens für die Verzweiflung in den Kellergewölben der Welt und erarbeiten deshalb ein Konzept, das nicht nur verschiedenste Erzählformen, sondern auch die Menschen aus Nord und Süd, Wohlstand und Elend, Licht und Schatten zusammenbringen soll, und dann passiert etwas, was am Anfang ganz wunderbar scheint und dadurch alle Aufmerksamkeit und auch alle Fördermittel auf sich konzentriert – weil es ja viel attraktiver ist, das Schöne zu dokumentieren als das Hässliche, das zu zeigen, was uns in ein gutes Licht setzt, statt das, was unser Schatten ist. Darum ist für „Black.Light“ mit einem Mal kein Interesse mehr da. Das Wunderbare, das vor einem Jahr seinen Anfang nahm, war der arabische Völkerfrühling. Was aber hat der mit „Black.Light“ zu tun?

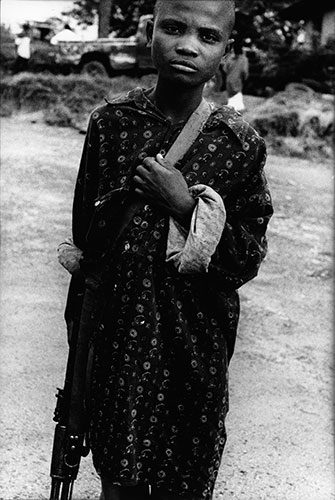

Zuerst muss man dazu fragen, was „Black.Light“ überhaupt ist. Die Frage zu stellen sagt bereits einiges über die Probleme aus, die das Vorhaben hat. Normalerweise sollte man annehmen, dass die grenzen- und disziplinenübergreifende Idee, eine Menschheitstragödie künstlerisch und dokumentarisch zugleich darzustellen, Neugier erregt und Unterstützung findet. Doch schon zu dem Zeitpunkt, als sich die Tragödie , um die es geht , abspielte , in den Jahren von 1989 bis 2007, wurde ihr außerhalb Afrikas nicht viel Beachtung geschenkt. Die Kriege der Nachfolgestaaten von Jugoslawien, der Nahost-Konflikt und zwei Irak-Kriege waren mehr als bloß publizistische Konkurrenz: Sie machten den Westen blind für die Schrecken in jenen Regionen, die nur Peripherie seiner Interessensphären sind. Für eine Region wie Westafrika. Dort wurden die Jahre 1989 bis 2007 durch Charles Taylor bestimmt. Der liberianische Warlord trug den Machtkampf um sein Heimatland erst einmal in dessen Nachbarstaaten, ehe er nach einem Bürgerkrieg 1997 tatsächlich Präsident von Liberia wurde, im Amt prompt den zweiten Bürgerkrieg und neue außenpolitische Konflikte schürte. 2003 wurde er durch internationalen Druck zum Rücktritt gezwungen, 2006 aus nigerianischem Exil ausgeliefert und 2007 vor einem Sondertribunal der Vereinten Nationen in Den Haag wegen Kriegsverbrechen in Sierra Leone angeklagt. Das Verfahren gegen den Mann, der es geschafft hat, Westafrika in Flammen zu setzen, läuft noch. Von den Folgen, die seine Taten dort haben, wo Taylor gewirkt hat, soll „Black.Light“ erzählen.

…

“

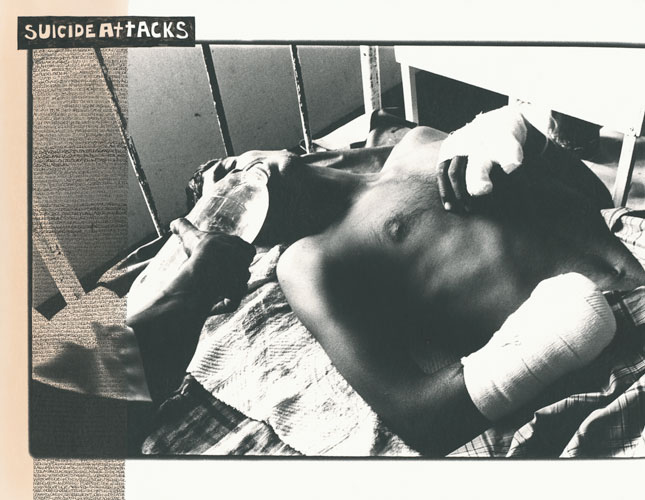

What defines an individual without connections? The definition comes from a daily reality continually occupied by the impossibility of travel and the successive fractures of love, by the utopia of reconstruction and cohabitation with horror, by the inexistence of the future and the violation of citizenship, by the death of dreams and the corrosion of objects, by the exhaustion of hope and the dismanteling of the group, the fragmentation of the body and the insularity of language. The persistence of war through bombs, mines, traumas, abandonment, isolation, pain, hatred, indigence, hunger, ignorance and fear makes it seem that the marrow of the human condition has been mortally wounded and the mankind has begun to reproduce a vacuum in their own genetic memory. God remains out there somewhere – perhaps with even greater strength given the impotence of his people in the abyss – but the lines of communication have also been cut, along with all the calendars and rites of communion

Sierra Leone, Liberia, Ivory Coast, South Sudan, Uganda, DR Congo, Ruanda, Ethiopia

For access to the entire reportage (images and text) please contact Wolf Böwig

The Charles Taylor Wars

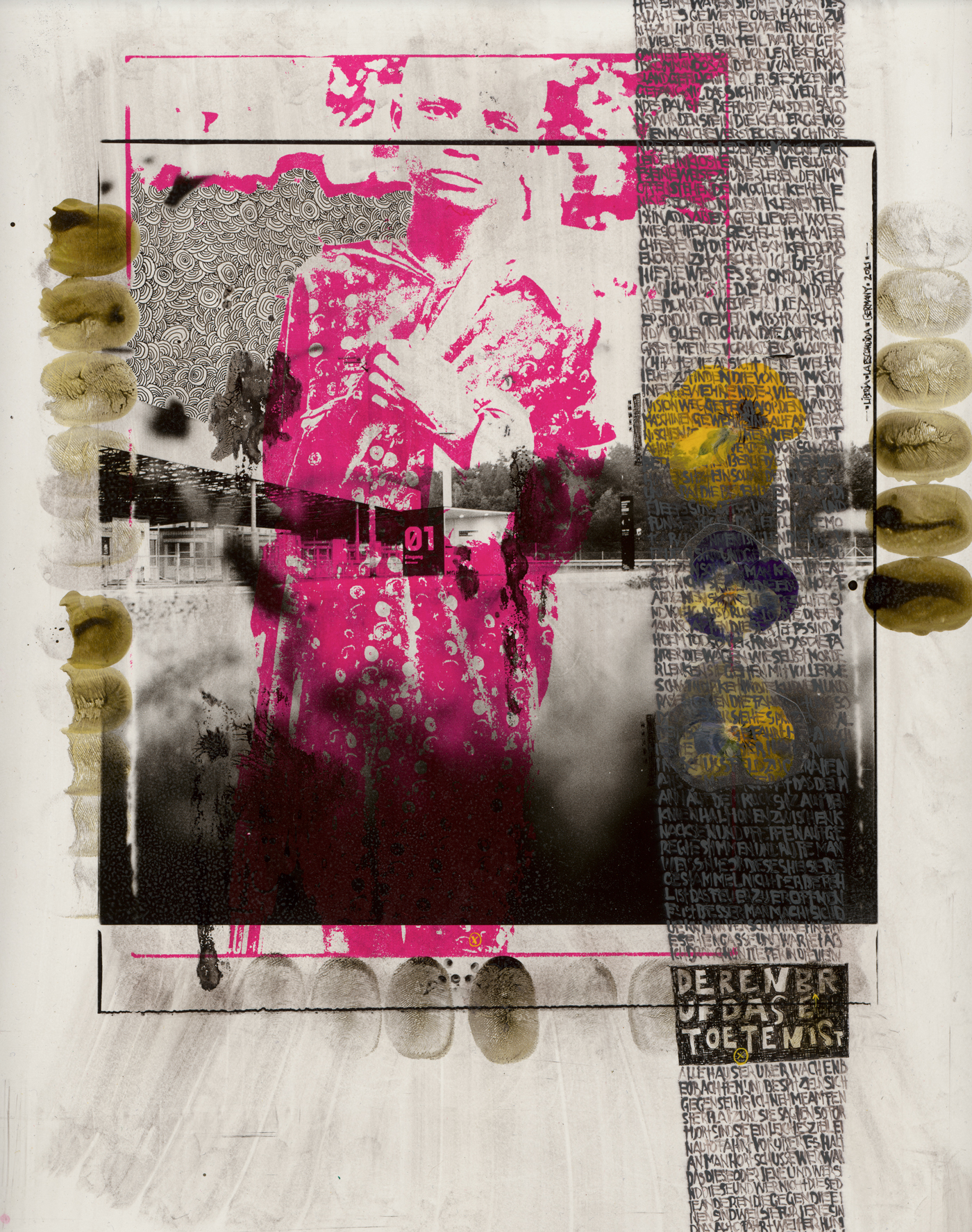

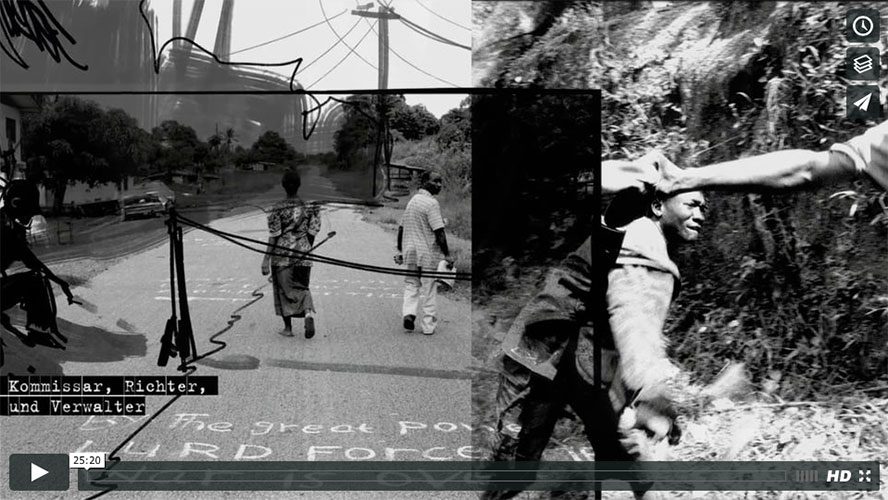

During the civil war between 1996 and 2003, Charles Taylor’s ‘warlord system’ brought suffering beyond human reckoning to Sierra Leone, Liberia, Guinea-Bissau and Ivory Coast, with hundreds of thousands killed in massacres and millions of refugees and displaced. For ten years Portuguese journalist Pedro Rosa Mendes and German photographer Wolf Böwig traveled the region to document these West African wars. Their work has been recognized and published in newspapers and publications around the world, leading to a Pulitzer nomination in 2007. The resulting reportages are often snapshots of incomprehensible horror from all fronts of these wars, while at the same time a sensitive approach to the plight of traumatized victims and perpetrators alike. During their many years of collaboration, Mendes and Böwig kept asking themselves the same question over and over again: How to present the incomprehensible, the unspeakable, the unimaginable through word and image. Is it even possible to document the breakdown of what we consider human at the same restore some of the victims dignity? under the label “The Charles Taylor Wars”, an international lineup of illustrators and artists create a crossover version of the reports, merging illustration, photography and written word. Through the collaboration of artists, photographer, author as well as local eyewitnesses, Black.Light Project creates the fragments for 15 different stories in a series of workshops. The work will be presented in galleries and public venues on three continents, Europe, Africa and the United States and later on published in a book.

Black.Light Project aims at creating synergies and a transcontinental dialogue that goes far beyond of what traditional war correspondence can achieve. Photography, journalistic reports, graphics and popular comicbook style merge into one homogeneous non-linear storytelling, creating a new publishing medium of its own.

„reporting violence“

…

When hatred whorls across a continent, it envelops people, daily life, it cuts off limbs, flattens villages, burns down buildings, and pushes hard against hope, belief. It is difficult to imagine the degree to which the world can turn upside down, and most of the time those of us not amidst or recovering from such destruction, don’t. We should. Not because it’s pleasant. Not because it’s easy or righteous. But because it’s the truth….

The film not quarantine one aspect of this multi-nation echoing. Black.Light acknowledges the scope of dimension that pain, loss, survival, and hope encompass by exploring it all in a braid of words, photographs, and illustration powerfully resonating together in the film. In addition to Böwig and Mendes, the collaborating visual artists include an internationally recognized and celebrated list of illustrators and creators with a presence in the legacy of the comic book and graphic storytelling fields, including artists from DC and Marvel comics.

…

Kirsten Rian

What defines an individual without connections? The definition comes from a daily reality continually occupied by the impossibility of travel and the successive fractures of love, by the utopia of reconstruction and cohabitation with horror, by the inexistence of the future and the violation of citizenship, by the death of dreams and the corrosion of objects, by the exhaustion of hope and the dismanteling of the group, the fragmentation of the body and the insularity of language. The persistence of war through bombs, mines, traumas, abandonment, isolation, pain, hatred, indigence, hunger, ignorance and fear makes it seem that the marrow of the human condition has been mortally wounded and the mankind has begun to reproduce a vacuum in their own genetic memory. God remains out there somewhere – perhaps with even greater strength given the impotence of his people in the abyss – but the lines of communication have also been cut, along with all the calendars and rites of communion

Afghanistan, Pakistan, Sri Lanka

For access to the entire reportage (images and text) please contact Wolf Böwig