Along the Grand Trunk Road

Twelve diary entries for our travel pages

“

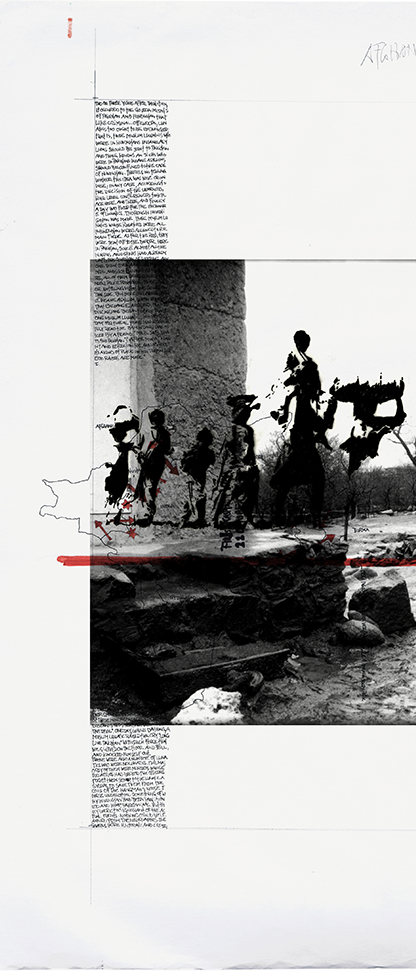

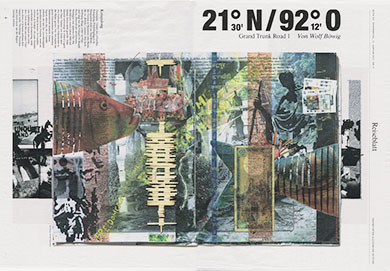

Wolf Böwig is a photojournalist, a war reporter who travels to the places that other people are leaving in droves. Euphemistically, he refers to them as conflict regions, but the horrors he encounters far surpass anything the term ‘conflict’ could possibly evoke. He covered the Yugoslav wars and the war in Afghanistan, and he was in Africa immediately after the Rwandan genocide. It is no accident that these are all corners of the world where the borders have been arbitrarily drawn and do not coincide with cultural, historical or ethnic areas, which, in turn, is one of the reasons why there is little trust in the state in these regions.

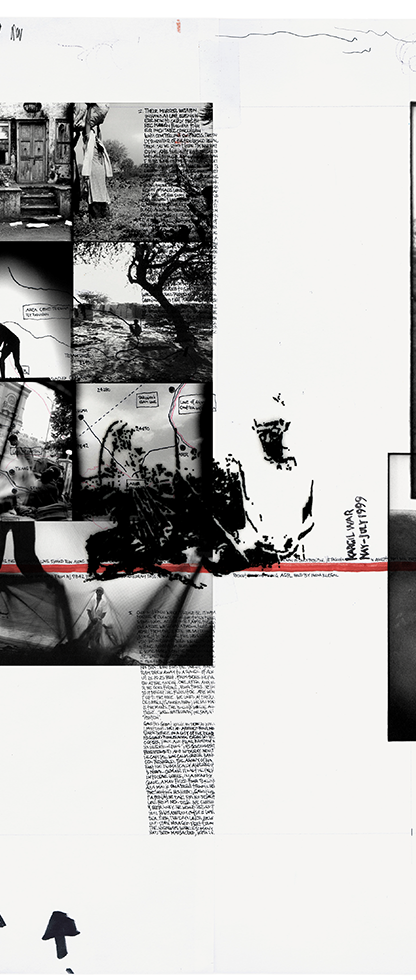

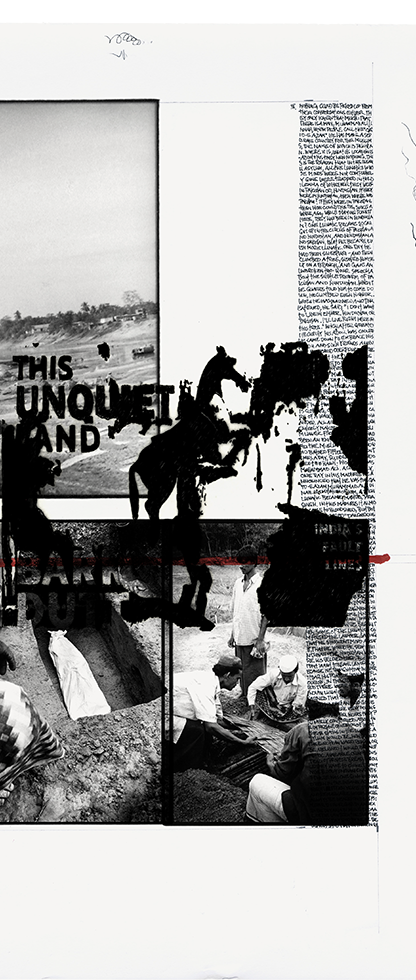

What Böwig saw and experienced in his travels often resembled scenes from a nightmare, and consequently his photographs regularly take us to the limits of what we can bear, and many go even further. What drives him, Böwig says, is a humanist mission which he has taken upon himself. He is not after the spectacular single image. Instead, he has been returning to many places every year for long-term reporting, and he has accompanied some people for a good part of his life. He used to work for Neue Zürcher Zeitung, for Le Monde and the New York Times, but there is no place in daily news journalism anymore for an approach like his. Now Böwig concentrates on producing and contributing to exhibitions, brochures and book projects, visual indictments through which he wants to raise awareness for the inhumanity of everyday life in the world’s warzones. In 2017, his last journey to date led him along the Grand Trunk Road from the Myanmar border through Bangladesh, India and Pakistan all the way to Kabul.

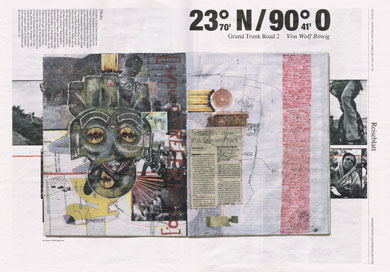

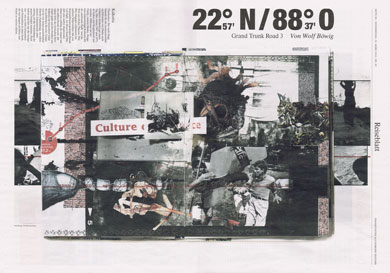

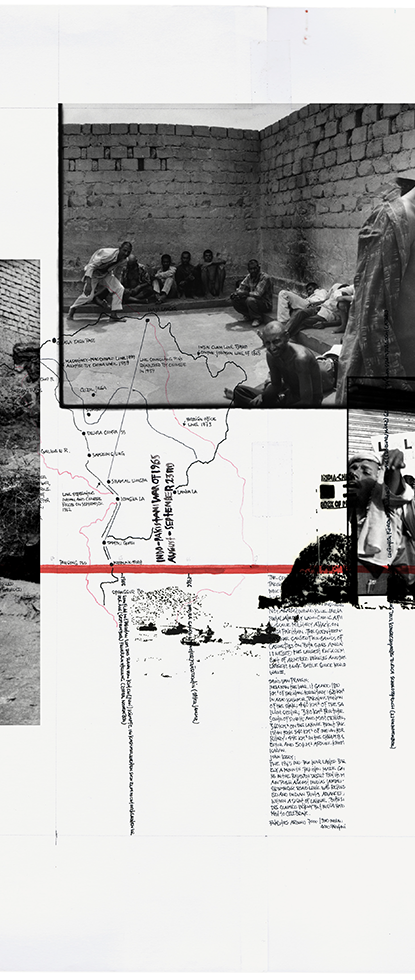

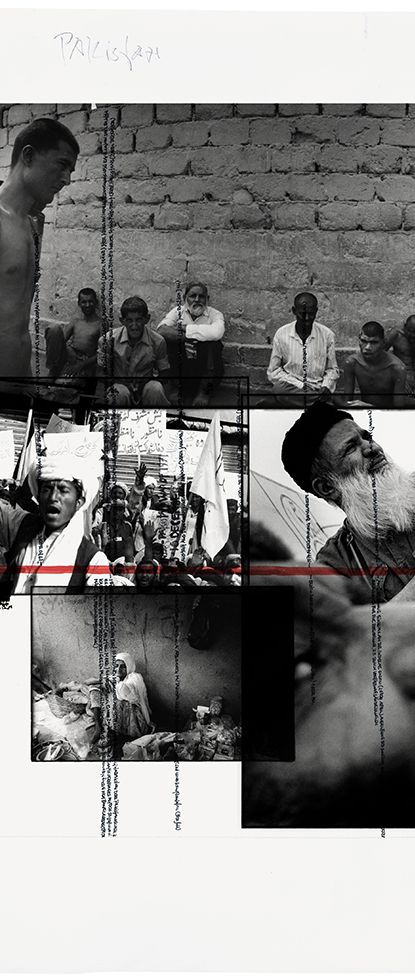

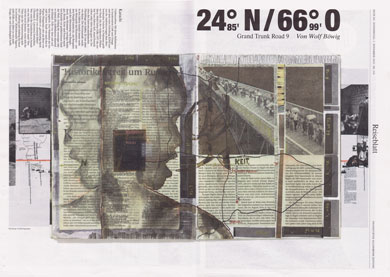

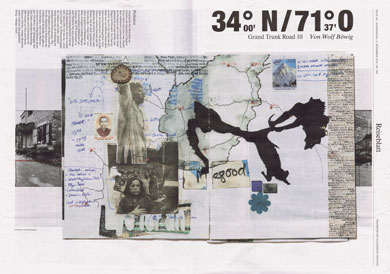

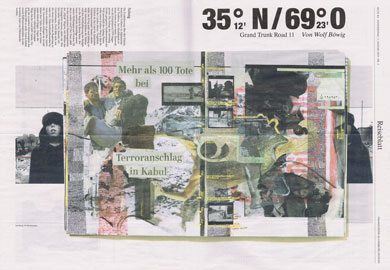

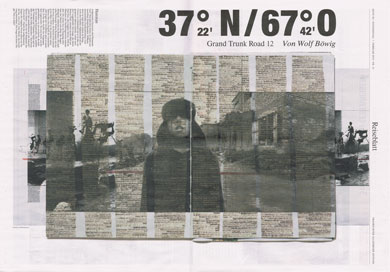

Böwig travelled along this route for five months on buses, by bicycle or on foot, not as a tourist, but as an observer, looking for the traces of economic, political and religious conflicts 70 years after the Partition of the subcontinent. He brought not much more than the clothes he had on, two cameras, three objective lenses, bags full of films, and the small tools for his diary: scissors and glue. From the little things that he found along the way and that seemed significant, Böwig produced collages which he collected in a folder. His materials were coins, photographs, newspaper clippings, matches and packaging, razor blades and pebbles. These collages are an artistic way of processing what he experienced, full of symbols and metaphors. Notes about his impressions complete the collages. Böwig calls these works a ‘departure for the inside’. Producing them is his personal method for finding calm at the flashpoints of world politics. Over the course of this year, twelve of these collages will be featured on our travel pages on double-page spreads, to retell Böwig’s journey three thousand kilometres from East to West across the entire subcontinent.

“

FAZ, 11. January 2018

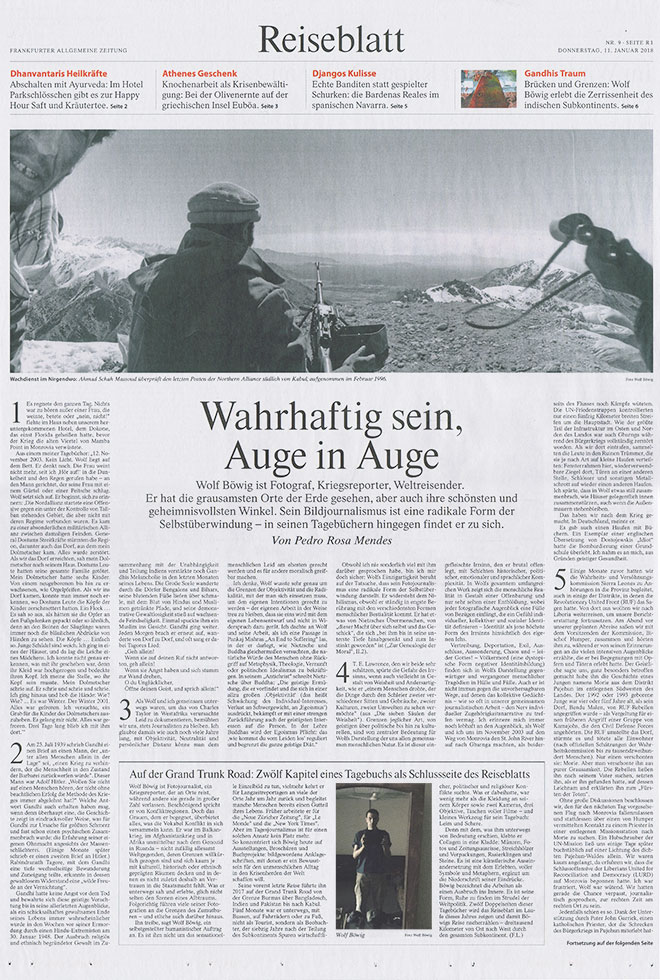

BEING TRUE, EYE TO EYE

“

Wolf manages a similar epiphany but using the inversed chemistry: our nightmares and fears are captured in the lives of others. Then, through revelation – a magic practice which Wolf never gave up -, they are offered to us in the form of supranatural strenght, divine wisdom, and intemporal grace.

They flow back from light and onto an emulsion of black and white images – and, in Wolf’s most recent work, of lettering and caligraphy. From coffin to vessel, photography being true, eye to eye.

“

Frankfurter Allgemein Zeitung

Nr. 9, Reiseblatt, 11. January 2018

REFERENCE

„Photonews“, 2018

exhibition Galerie Peter Sillem, Frankfurt 2018

VG-Bild Stipendium, 2016

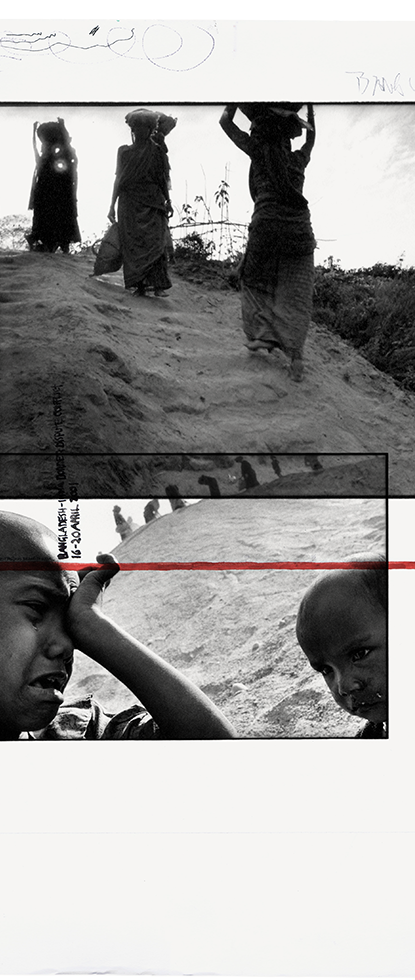

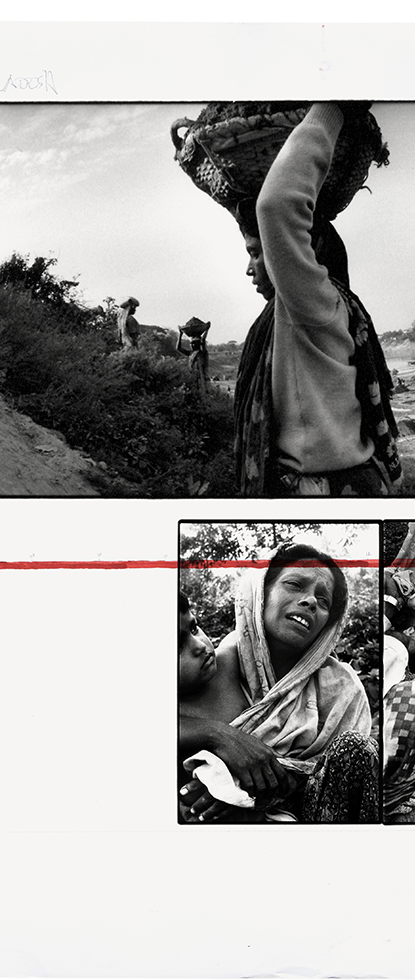

Kutupalong

Stranded. Not far from the official Kutupalong refugee camp, there is a ruin called ‘the bridge’ by the Naaf river, which marks the border between Bangladesh and Myanmar. What sounds like a symbol of hope just leads into the river and merely serves as a jetty where illegal boats are moored, carrying too many displaced Rohingya from the opposite bank. Even back in 2008, nobody on either side wanted these disenfranchised people. Many had to dwell in improvised camps by the river with no services whatsoever. The names of dead Rohingya have been carved into the piers, likes harbingers of a genocide. This place shines a clear light on the fragmentation of the Indian subcontinent. Tagore seems to have had an inkling of this, when he wrote to Gandhi that the concept of non-violence would not guarantee freedom once it had achieved power. A half-finished statue of Gandhi stands in his ashram in Noakali, only a few hours northeast of Kutupalong. The city’s capacity to honour the founding father and his vision is limited by the immediate need to help more and more refugees, paupers and members of warring factions from the region.

Dhaka

Charged. In the old alleyways of Dhaka, Bangladesh’s rapidly growing slum metropolis along the banks of the polluted Buriganga river, Muslims, Hindus and Christians live at close quarters. Hardly a day goes by here without provocation, destruction or murder. Religious, social and political issues have become inextricably linked. The main conflict is the discrimination of Bengali Hindus as traitors since the 1971 War of Independence. Their current enemies are well-connected Islamists, who have found a welcoming haven in Old Dhaka. During Ramadan, their printing presses are churning out more copies of the Quran than there were machetes during the Rwandan genocide. Gandhi’s ideals are as remote here as the regal wisdom of the revered elephants. The situation is reminiscent of Melville’s story Bartleby, the Scrivener. While the central character’s motives for refusing to do what is asked of him are obscure, everything seems to be inexorably heading towards the next escalation.

Kalkutta

Overtaxed. If you do not take the plane, it will take you a little over a day to travel the 155 miles from Dhaka to Kolkata. In 1947 and in 1971, when India and Bangladesh were founded, millions were fleeing along this route, most of them Hindus. Bengal’s melting pot Kolkata was a dying city and the world shared its suffering with Mother Theresa. But another symbol of the city shines like blood: The Lal Dighi water reservoir, lined by buildings from the colonial era. Almost as if by accident, a cleanly severed hand at the water’s edge brings the violence, which periodically erupts in the city, into clear focus. A unique spirit of political unrest, like a ghost from the British colonial past, haunts the streets of Kolkata. This spirit can also be felt in the deprived Narkeldanga district, where even back then tens of thousands waited longingly for the proclamation of the new freedom. But the majority here has never been liberated, like so many stranded and homeless people in a city which seems to have been waiting for its rebirth to start for a very long time.

Shimla

Partitioned. It takes hours until the overcrowded train has dragged itself up to an altitude of 2,000 metres in the Himalayas in northern India. After hundreds of bends, bridges and tunnels it reaches the British Crown’s former summer residence. Today, safe return trips can be booked from Shimla. But the calm is deceptive. Like Rome, this city was built on seven hills, and, also like Rome, it has seen as many negotiations as it has seen dissatisfied parties. Over the 20th Century, three treaties with their lines of control have cut up the proud regions of Kashmir and Tibet. Like the frequent lightning strikes tear up the threateningly dark mountain skies, these lines of control have struck deep wounds into entire states. Three wars did not bring peace. India and Pakistan still continue to light the fuses leading to the powder keg that is Kashmir. The sparks are coming from long-tolerated autonomy, arbitrary partitions, state oppression and religious conflicts. Even after 40,000 dead over the last thirty years alone, Stones of Fury are continuing to fly in the capital Srinagar, as Frontline magazine has it.

Delhi

Backed up. Connaught Place in the heart of New Delhi – a perfect circle, an aureola made up of important thoroughfares and consisting of several rings generously dotted with buildings. This 100-year-old oasis of modernism represents a colonial dream: India as a planned city. But this dream was shipwrecked by the shrewd obstinacy of freedom fighters like Gandhi or Talwar, the master spy. Under the name of Silver, he dexterously commuted between Afghanistan and India, sent false messages to Nazi Germany from the King’s palace and managed to keep five major powers busy. A model for the entire country: The subcontinent had to practice its democracy, a democracy characterised by strong leaders and flexible rules. Of late, Hindu Nationalism has taken over the capital, with Modi as its superhero at the helm. In 2002 in Gujarat, Modi allowed the anti-Muslim pogroms to happen. His triumphs are redrawing the conflict lines. Today, anyone who eats beef or practices Islam or, heaven forbid, does both, is seen as a traitor. When religion becomes political like this, tolerance quickly gets submerged by violence and loses its ability to draw wider circles.

Amritsar

Trapped. Amritsar is the first city in today’s India along the Grand Trunk Road, just a few kilometres from Lahore in Pakistan. It is lit up by the reflection of the Golden Temple, the most holy site in Sikhism. Inside, paintings tell the Sikh story as martyrdom, a history of suffering at the hands of Hindus and Muslims, the British and the Indian state: hung in their hundreds during the 1919 massacre with nowhere to escape, shot in their thousands during the battle for the Temple in 1984. But it is not that simple. The warlike Sikhs served the British willingly as soldiers. They murdered in the railway carriages that were taking Muslims from India to Pakistan 70 years ago. Those who had to sit on the roofs could not escape the wires that had been strung up near the border. The Dawn of Freedom trapped in a maelstrom of violence and revenge. Unintentionally, a dusty model train made from cardboard becomes a symbol for the blood-drenched route. But on the way from the murder of Indira Gandhi to Manmohan Singh becoming the first Sikh to lead India, this path has also been lined with a glimmer of hope.

Wagah

Gone mad. From Amritsar, it is a day’s walk to Pakistan. Since 1947, the Radcliff Line has run through the Punjab like a scalpel’s cut, while both sides still depend on its waters. Again and again, military installations block the view on the way. The feet feel the ground, which is full of the bones of Hindus and Muslims, victims of that tragic, out-of-control exodus of millions. Pakistan’s new Prime Minister back then said: ‘Our people have gone mad.’ Those who reached the Wagah border crossing could at least hope to have survived, but their old home was now as far away as their new one. For the lunatic Bishan in Manto’s story Toba Tek Singh, there is only one final real place left: the no-man’s land between the border fences. Today, a two-part stadium stands in this spot, with flag posts reaching into the sky, grandstands reminiscent of Ancient Rome and entertainers leading the audience in frenetic clapping. When the border is closed at night, the flags of both countries are lowered at exactly the same pace, one millimetre at a time. The border guards’ bizarre spectacle can blur the line between war and peace. But everyone smiles on their selfies.

Lahore

Seeking. The British avoided the narrow, labyrinthine alleys of this city steeped in history. They built their own city just outside its old walls, complete with a museum for its ancient Buddhist culture. Even today, the world still feels far away in this House of Wonders. But anybody walking through Lahore’s old town district today can feel the tragic beauty of a city teetering between deep spirituality and hard politics in the same way that Rudyard Kipling’s character Kim did in the late 19th Century. Kim had a choice to make: to follow the White Lama or to give in to the thrills of espionage. Little wonder that both national movements laid claim to their own states in Lahore: the Indian one in 1929, and the Pakistani one eleven years later. After partition, Lahore became a battlefield and was ethnically cleansed in an apocalyptic scenario that would play out in a similar way in many other places around the world: East Timor, Rwanda, Sierra Leone, the Balkans. If we take a closer look at Lahore, we can gaze into the abysses of our western souls – it tears us apart, confuses us and never again lets us go. We must leave this place because nothing here will provide us with any answers, least of all our desire for what has been lost.

Karachi

Unmissable. With their shining yellow and orange reflectors and the red letters EDHI on them, ambulances defy the insane traffic of Pakistan’s largest city. In 1957, when the revered philanthropist Abdul Sattar Edhi put the first ambulances on the streets of Karachi, the city had been shaped by the influx of Muslim refugees from India for ten years. Edhi was one of them. In the years that followed, Karachi, once merely a provincial capital, was gradually transformed into a metropolis for the uprooted. People moved there from the Punjab, from Bengal after it had been cut off from Bangladesh, and persecuted Rohingya came from Myanmar. The rhythms of economic booms, crises and coups made Karachi the most dangerous city in the world. In the early 1990s, all of the city’s ambulances were permanently in use. Edhi was both near and far at the same time. He saw the madness of violence in his city, as well as in Papua-New Guinea or at the Horn of Africa ‘through the veils at once of two customs, two cultures, two environments’ (T.E. Lawrence). Who will be the custodians of history in the way that Edhi was, who died in 2016? Who will still know who the perpetrators were when they try to shed their responsibility? Like any witness in court hoping for justice, Edhi watches us, ‘shaking and shaking his head in irritation’ (Rabindranath Tagore).

Peshawar

Game over. The people living near the legendary Khyber Pass have always made their living from trade. But instead of deep blue Armenian stones and fine Persian rugs, the wares on offer today are hand grenades and drugs by the kilogram. The state is as far away as the peak of K2. This area, the eastern edge of their autonomous tribal regions, is ruled by the Pashtuns. For them, the border between Pakistan and Afghanistan is merely a permeable fiction dreamt up by a state they do not recognise. In the 19th Century, the Pashtuns were the winners of the Great Game, the tug-of-war between the British Empire and Russia over this strategically important region. And this victory has been replayed several times since 1979: With a bang, Peshawar was transformed into the dangerous epicentre of Islamist terror. Ahmad Shah Massoud, the Lion of Pandjshir and personified hope of democratically inclined Muslims, lost his life to terrorism in his fight against the Taliban as early as 2001. The people of Peshawar love Buzkashi, a traditional game that can seem like a metaphor for the violence in their society. On horseback, players compete for the body of a dead goat with no holds barred. But the riders do not play for themselves, they are dependents. Rich clans have combined the struggle for honour and power with bribery, gambling and money laundering. Just a few steps away or a few moments later, this simulation of a battle can turn into the grim reality of war.

Salang

Beaten. The disenchantment with the deployment of German soldiers to Afghanistan is rooted in a long tradition. Little to nothing has ever been won in the Hindu Kush, but in 1979 the Soviet Union was quite assured of its impending victory and built what was for a time the highest road tunnel in the world, just underneath the Salang pass. The tunnel was intended to give the Soviets easy access to the south of the country, but it did not. Since then, Afghanistan has been in a permanent state of emergency. Periodically, the war keeps returning to Salang as well. For years, the Taliban and their radicalisation of religion made the region a pariah, and to this day, bombing attacks regularly destroy all hopes for peace. Will Salang, the refugee girl from the mountains, ever get to experience it? The state does not hold much sway anyway in the autonomous tribal areas of the AfPak region, as military strategists refer to this part of the world. You need deep faith in God here if you do not have a gun. And you do not want to get on the wrong side of either government. Secret service thugs are only too keen to demonstrate to each other who is in charge. When they strike and leave their victims lying by the border fence, crossing over into the other country will take much longer than it would have anyway and will not be possible without opium for the pain and soldiers playing cynical games with firearms. And in Kabul you have to be just as lucky if you want to escape a suicide bomber.

Hairatan

Wide open. Border crossings are positioned in no-man’s land and are full of interchangeable features: checkpoints, welcome signs, peace bridges. And yet you still find yourself in the middle of a war. Over the last few years, this war has also reached the border region with Uzbekistan in Northern Afghanistan. This is a place where life gets blown to pieces. A boy, walking through ruined streets, is reminiscent of a print entitled Angelus Novus by the artist Paul Klee. Klee produced it in 1920 in Munich, surrounded by the upheaval of the post-war period. Its subject is depicted with raised arms, as if to give a blessing, with his mouth wide open and unnaturally big eyes. He could be an orator. But the Jewish philosopher Walter Benjamin saw something very different in the figure. In March 1940, while in exile in Paris, he wrote in Paragraph IX of his essay ‘On the Concept of History’: ‘This is how one pictures the angel of history. His face is turned toward the past. Where we perceive a chain of events, he sees one single catastrophe which keeps piling wreckage and hurls it in front of his feet.’ A storm ‘irresistibly propels him into the future’. For Benjamin, this storm was ‘progress’, and it is through the wide-open eyes of the New Angel that we see it for what it is: a force which leaves destruction in its wake. The boy has no wings. What does he see?